The Scaremongers

They fuel fears, warning that more stringent regulations could be deleterious or even deadly to consumers, and they have a direct line to top politicians. How lobbyists in Berlin and Brussels are working to prevent thorough testing for medical devices.

Florence is suffering. The elderly blond drags herself along a hospital corridor in her dressing gown before sitting down and gazing into the camera with vacant eyes. She is in need of a life-saving operation, but the narrator warns that a new European Union law, the Medical Device Regulation, would mean that someone like Florence has to wait three years for the operation she needs. Florence, a message on the screen makes clear, doesn't have those three years. In other words, Florence would have to die because of the bureaucrats in Brussels.

That, at least, is the story told by the 2013 video clip.

The truth, though, is that Florence isn't actually sick. She's an actress, and her portrayal of a mortally ill patient is all part of a professional media campaign whose aim was to preserve the status quo when it comes to bringing pacemakers, artificial knees and insulin pumps onto the market. Anything to avoid stricter regulations and costly studies.

A video insinuating that people will die because of stricter regulations: Even the most hard-nosed members of European Parliament describe the lobbying campaign by the European association Eucomed in 2012 and 2013 as unprecedented.

imago

"I was in Brussels for 25 years, but I never experienced that kind of lobbying pressure before," says Dagmar Roth-Behrendt, 65, who served as a delegate to European Parliament for the center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD) from 1989 to 2014.

As a rapporteur in parliament, it was her job to help draft the new EU regulation on the certification of medical devices. In addition to the video, there were also ads taken out in newspapers and aggressive lobbying efforts directed at EU parliamentarians. "It was the lowest of the low, really disgusting," says Roth-Behrendt.

It is, of course, undisputed that medical devices save the lives of millions of people each year. At the same time, though, Europe has been at the center of some of the worst medical device scandals in recent history. Between 1995 and 1999, for example, women received breast implants containing a harmful filling made of soybean oil. Europe is particularly vulnerable to scandals of this type because of the nature of its certification system for medical products: It is privatized and unreliable.

Unlike drugs, implants and prostheses only have to be tested to confirm whether they actually function from a technical standpoint and not whether they are actually beneficial to patients. It's not government agencies that determine what may or may not be implanted. Rather, certification of these products is left up to private companies known as "notified bodies" -- like Germany's TÜV or DEKRA. They mostly just review the documentation, but not the devices themselves. These companies only earn money if they receive a testing commission from the manufacturers.

That's why many companies first introduce their products in Europe before attempting to release them in the United States, where regulations are much more stringent. One example is PleuraSeal, a lung sealant designed for use in surgery to prevent air in the lungs from leaking into surrounding tissue. Ultimately, though, it didn't seal as well as planned. Another is Robodoc, a surgical robot from Integrated Surgical Systems (ISS) that ended up causing injuries to a number of people. The manufacturer did not respond to requests for comment.

In 2011, Jeffrey Shuren of the U.S.' FDA regulatory authority said that patients in Europe were being used as "guinea pigs."

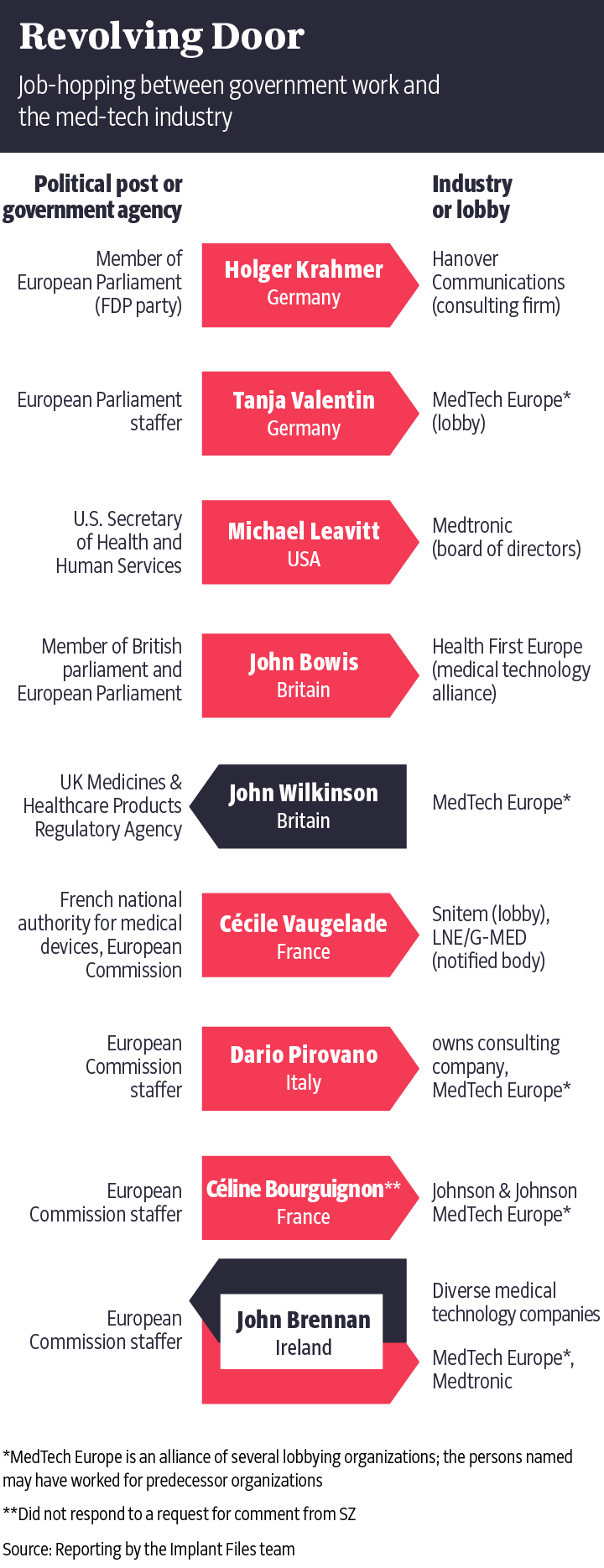

Medical devices are a multibillion-euro industry. In Germany alone, more than 12,000 companies are involved in the research and manufacture of everything from simple wooden tongue depressors to complex spinal prostheses. Four lobbying associations tend to the industry's interests in Germany: the Central Association of Medical Technology Dealers, Manufacturers, Service Providers and Consultants (ZMT), the Diagnostics Industry Association (VDGH), the medical technology division of Spectaris and, finally, the German Medical Technology Association (BVMed), the largest and most influential lobbying group. Three are members of the European umbrella organization MedTech Europe, which has a singular overarching goal: Preserving the status quo.

The European Commission, the EU's executive body, first sought to change the system back in 2008. Brussels wanted to ensure that faulty implants would never again be installed without having been tested. Never again should phased-out breast implants be allowed to injure thousands of women, or defective pacemakers to deliver deadly electric shocks to their wearers. As in the U.S., products were to be systematically tested for clinical use, with a government authority overseeing the process. Particularly risky products were to be tested by the authorities, and no longer by private companies.

Medical associations, consumer watchdogs and patients' rights organizations were all hopeful about the EU's efforts in 2008. MedTech Europe, on the other hand, was indignant. "Patient care and access to new technology is, in our view, likely to suffer," the lobbyists warned the European Commission. The proposals, it said, were "alarming," "objectionable" and "completely unacceptable."

The lobbyists made it sound as though patient well-being would soon be a thing of the past. They warned of an emerging bureaucratic monster in Brussels that was about to drive small- to medium-sized businesses into the ground and grind progress to a screeching halt. The lobbyists launched an offensive.

When then-European Commissioner for Health and Consumer Policy John Dalli went before the press four years later in February 2012 with calls for "improving patient safety," it became clear that his initial ambitions had been watered down. Earlier complaints that the existing approval system was insufficient had given way to language asserting that the rules as they stood were by no means "fundamentally unsound." The apparent reasons for the redonning of the kid gloves could be read between the lines: There had, for example, been "targeted meetings at senior level with representatives from industry associations and with Notified Bodies," a European Commission working paper from September 2012 states. Who met with whom and when was not revealed in the document.

The same working paper noted that medical devices reach the market faster in Europe, "whilst the safety levels were considered equal." But the study cited to back that finding came from the Boston Consulting Group, a company whose work is financed by myriad lobbyists in the U.S.

"It was important to me that not just drugs are safe, but that medical devices are safe as well," former European parliamentarian Roth-Behrendt told the Süddeutsche Zeitung and the German public broadcasters NDR and WDR in an interview. Some 500 million people live in the European Union and they could all benefit from stricter regulations. Implants that are more thoroughly tested would mean fewer complications, lower costs for insurers and, in the end, lower premiums for the insured. Or, to put it simply: A longer and better life.

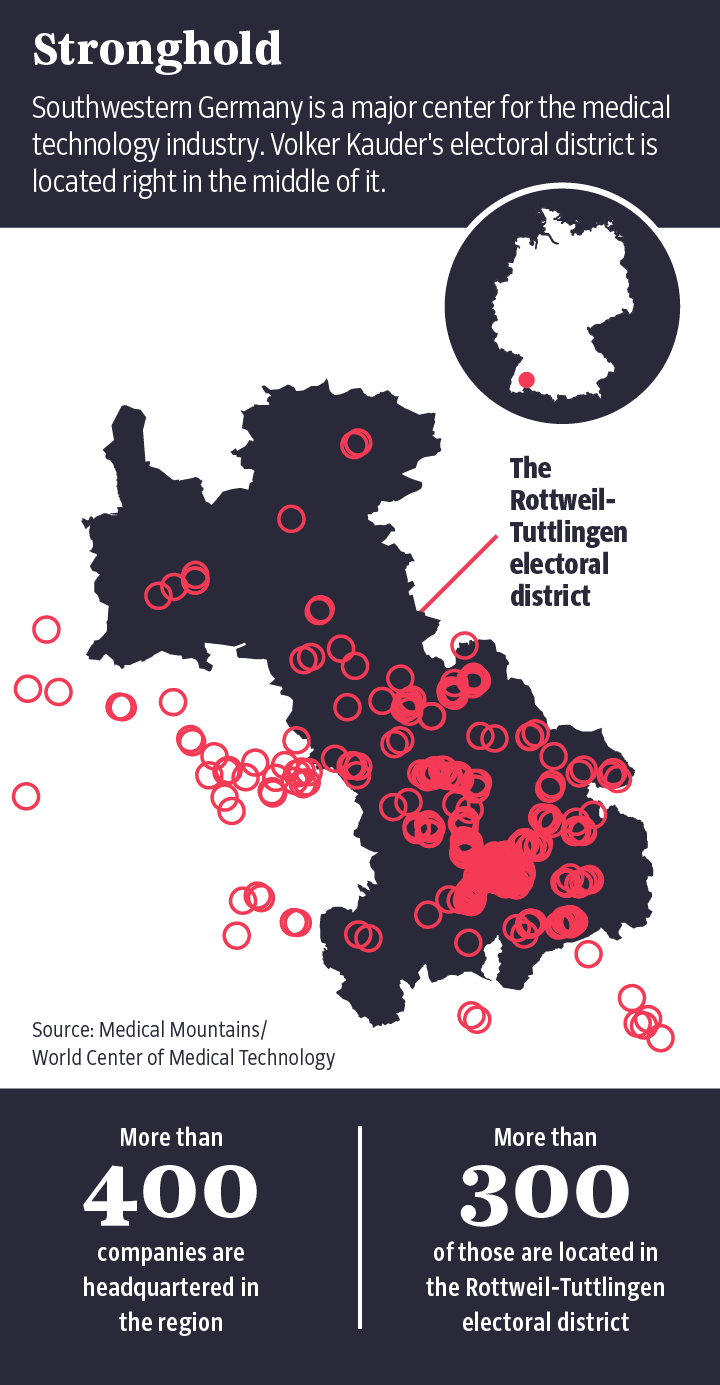

For manufacturers, though, stricter rules mean higher costs and longer delays until a product reaches market. If government authorities were to take control of the testing process, it would kill the notified bodies' business model. That fear became tangible again this summer, when representatives of several dozen companies met at the civic auditorium in Tuttlingen. Probably no other part of Germany is home to as many medical device manufacturers as is Tuttlingen, located in the southwestern state of Baden-Württemberg. The town also happens to be part of the constituency of Volker Kauder, a senior member of the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU), the party led by Chancellor Angela Merkel. Kauder is considered a firm Merkel loyalist and was leader of the conservative group in federal parliament until September of this year.

Medical Mountains is the name of the association representing the Tuttlingen-based medical device companies, and they are well-versed when it comes to exerting their influence. Martin Leonhard, for example, works for the endoscope manufacturer Karl Storz and is also chair of the medical technology division of the Spectaris lobbying group. "I have been very active in the political discussion since the drafting of the Medical Device Regulation in 2012 and have represented the interests of companies and associations in Brussels, Berlin and Stuttgart," Leonhard told his colleagues in Tuttlingen's civic auditorium.

Pressematerial Storz/Bildbearbeitung von SZ

During this critical phase of the EU legislative process, Leonhard didn't just set up meetings for Kauder with representatives of local companies, but also for other key politicians -- policymakers like Jens Spahn, who coordinated health policy for conservatives in parliament at the time and who is now Germany's health minister, and Annette Widmann-Mauz, who until March 2018 served as a high-ranking official in the Health Ministry. In reflecting on the gains made by the lobby in five years of discussions over the Medical Device Regulation, Leonard noted to his audience in Tuttlingen: "There is no centralized European approval authority." And, "there is also no use assessment."

It hadn't been easy, Leonhard said, because "Ms. Roth-Behrendt," the SPD rapporteur in European Parliament, "made a massive push for more stringent regulations." Another problem, he noted, was that many European countries "primarily represent the patients."

Volker Kauder is acutely aware of the needs of medical device manufacturers. At the European level, for example, he is said to have advocated for the retention of a special rule that essentially allows companies themselves to issue the so-called CE Marking -- which indicates compliance with regulations -- for scalpels and other less risky surgical instruments. The kinds of companies that are plentiful within Kauder's electoral district. A kind of "Lex Tuttlingen."

A 2014 position paper from the Health Ministry, which has been seen by the Süddeutsche Zeitung newspaper and the broadcasters WDR and NDR, states: "Mr. MdB (member of German parliament) Dr. Kauder has already contacted the minister regarding this matter."

The minister in question was then-Health Minister Hermann Gröhe, also a fellow CDU member. In March 2016, a department head wrote in an email that the ministry would do its part to ensure that surgical instruments would continue to be excluded from having to be tested by a certification authority, "not least because of interventions by MdB Kauder." When contacted, Kauder declined to comment on the matter.

If you sit down with officials from BVMed and Spectaris, both members of MedTech Europe from Germany, you will hear one thing above all: How good their political connections are in general and to the Health Ministry in particular. They say several conversations take place every week with ministry representatives, while the health minister and his senior deputies are always ready to listen.

More critical voices, such as that of Harald Schweim, the former head of Germany's Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM), say:

All the lobbyists have to do is "whistle" and politicians "heel. They're more obedient than my dog."

That statement would appear to be supported by hundreds of pages of previously unseen documents from the Health Ministry that have been reviewed by the Süddeutsche Zeitung, NDR and WDR. They paint a picture of a ministry that sometimes swallows industry arguments whole without question and can occasionally seem to lose sight of patients' well-being. One example: During a discussion over whether manufacturers should be required to prove in the future that their product is medically useful, an internal email from a department director in the Health Ministry dating Nov. 16, 2011, states: "But this isn't currently required in any market in the world and this totalitarian approach would violate fundamental principles of the free market economy or competition."

It was around this time that Florence joined the fray with her feigned illness. Exactly 277 days after the video featuring her went online, the European Parliament voted in October 2013 to approve a watered-down version of the Medical Device Regulation. The final version would not include a requirement for a government certification authority or the obligation to test medical devices for their clinical usefulness to patients. Dagmar Roth-Behrendt, who had wanted to see tougher rules, had lost. "It makes me so angry that I could just cry," she says today.

Despite several years of negotiations, the systemic change that many had been hoping for failed to materialize. Rather than government authorities, it is still private companies that decide on the certification of medical devices. There is also no requirement for new devices to be reviewed for medical usefulness. But the notified bodies are now required to conduct unannounced inspections of the manufacturers -- every five years. It's a binding rule that hadn't previously existed.

MedTech Europe saw this as reason to celebrate. At a conference in the autumn of 2017, a representative of MedTech Europe welcomed the outcome, saying that "major blockers to innovation" had been "deleted or balanced." A state licensing authority like the Food and Drug Administration in the U.S.? There wouldn't be one. Clinical tests that prove the effectiveness of the devices? None of those either.

Florence has reason to be pleased. It may have emerged since then that the miracle treatment she was seeking isn't as effective as hoped. But there is one the campaign has demonstrably achieved: When it comes to the protection of patients, she has helped keep the government at bay.