Hans and Barbara were very much in love. “We were born married,” they would say. They were always together, and when it was time to go, they passed away at almost the same time. He died in January and she in September.

Only afterward did their daughter Kendra understand that her parents had shared another passion in life – one that drove Hans Heymann’s fight against the Nazi injustices that befell his family. He fled Hitler’s Germany for the United States as a youth and often spoke of the 41 Max Pechstein paintings and 120 drawings that his parents had left behind in Berlin, and about how eager he was to recover that treasure. Pechstein’s art was so much a part of his family that on one occasion, Heymann bought an art calendar with prints of Pechstein artworks and framed them for his children.

Kendra chose “Fishing Port in Bornholm” and hung it on the wall, but as a young woman, she wasn’t particularly interested in the details. “I knew they were very caught up in it, but I always thought: If I asked them about it, they would talk for hours.” Kendra, whose maiden name was Heymann but now goes by Sagoff, says: “It was only after their death, when I read their letters, that I realized the huge amount of work and devotion they had put into it. I wanted to weep with regret that I hadn’t noticed before.”

Kendra Sagoff is a shy person who has always preferred to stay out of the public eye. “I’m usually guarded, but when I’m not, I let it all out,” she says. And for the first time, she now tells the story of a wonderful German-American friendship – the story of two families on either side of the Atlantic searching for a lost treasure, a search that is now in the third generation. And even though their quest has known almost nothing but failure for decades, they haven’t given up. It is a story about how the horrific injustices perpetrated by the Nazis continue to be felt and how surprisingly satisfying it can be to stand up to those injustices today.

First Generation

It all started with Kendra’s grandfather, Hans Heymann, Sr., the product of a Jewish-German family full of formidable personalities. He was a political economist who founded an insurance company. One of his brothers was the composer Werner Richard Heymann, who wrote the old German standby “Ein Freund, ein guter Freund” (“A Friend, a Good Friend”). Another brother was named Walther, a poet and art aficionado who volunteered to fight in World War I out of love for his fatherland and died on the front.

To honor his brother, Hans Heymann bought several paintings by the expressionist artist Max Pechstein. In describing Pechstein’s art, his brother said that he had never laid eyes on anything more exceptional. Pechstein, meanwhile, dreamed of breaking down barriers. Art, he said, should no longer be the pleasure of a few, but the “happiness and life of the masses.” The group of artists known as Die Brücke (The Bridge), to which Pechstein belonged, sought to lead “from one shore to another.”

Privat / VG-Bildkunst, Bonn 2018 I Pechstein Hamburg / Tökendorf

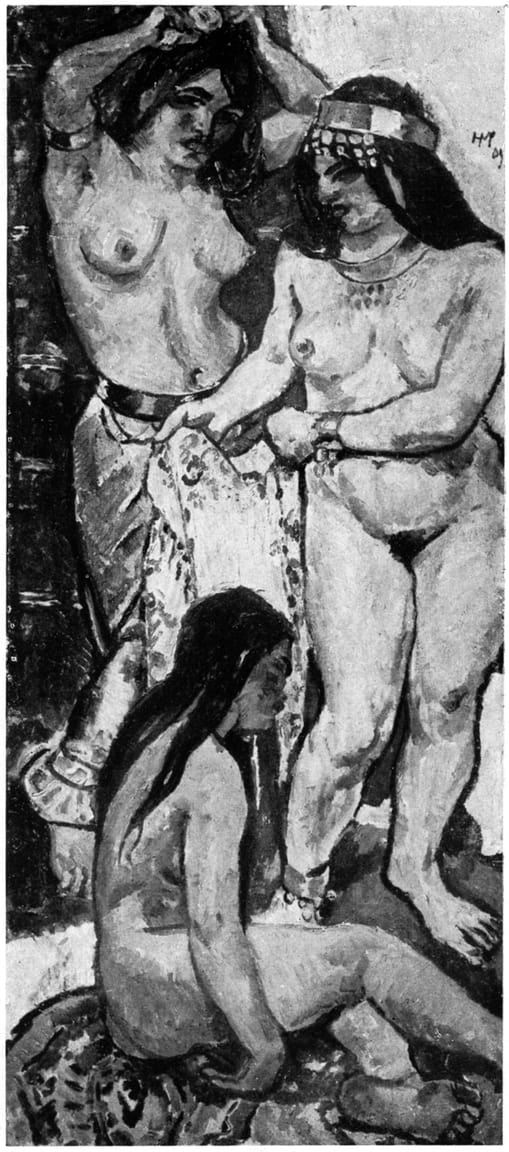

Pechstein was seen as powerful, affirming and carefree and his paintings were a sensation. When the painting “The Yellow Veil” was shown in Berlin, one critic described it as being so provocative that it was best to admire it from a distance. “The wild fleshiness of the … women,” the critic wrote, is “the utmost in sensual insouciance.” Heymann bought the painting along with many others and christened the compilation the “Walter Heymann Memorial Collection” – a declaration of love to his deceased brother and to a revolutionary artist.

Then Adolf Hitler rose to power. Hans Heymann fled from Germany to America in 1936 with his son Hans, Jr., and his wife Ella joined them a year later. As the family arduously sought to establish new lives on the East Coast, the Nazis were rummaging through the Heymanns’ property in a Berlin storage facility. At the end of 1941, the regime confiscated all the family’s belongings and auctioned them off, though dozens of the “degenerate” paintings and drawings from Pechstein were left out of the sale. The Reich Chamber of Fine Arts, a Nazi-era state agency focused on promoting the visual arts, ordered that the Pechstein paintings be recycled. The paint was to be destroyed while the frames and canvases were to be distributed for reuse among “students in need.” At the last minute, though, the paintings were spared: In early 1942, a cultural affairs department of Hitler’s NSDAP party demanded the artworks for “scientific purposes.” It is unclear what happened to them after that.

On May 8, 1945, when the horror of war came to an end, Hans, Sr., sent a letter to his brother. “I am not yet fully awake from the nightmare in Europe,” he wrote. “Everything we have heard and seen is so disgusting.” His German homeland had become so foreign to him that he wrote in English. “I rarely think of Germany and I am not longing to go back either."

No, he didn’t miss Germany, but he did yearn for his Pechstein collection. His granddaughter Kendra explains using a quote from his letter: "What an abyss has opened between the past and the present,” he wrote. An abyss between his old life in Berlin and his new life in America. His collection was “the bridge over the abyss,” says Kendra Sagoff. It was his way of bringing the two worlds together, the new one and the one he had lost.

Heymann, an incurable optimist, began looking for the collection. He got in touch with the Allies and, three years after the war, contacted the artist himself. “Dear Max Pechstein,” he wrote, “you will surely recall that I acquired a unique collection of your paintings. I have endeavored for several years to regain possession of our property.” He asked Pechstein for help. But both men were nearing the end of their lives and the chaos that was once Germany was simply too profound. Even Heymann, ever the optimist, gradually succumbed to disillusionment. He never learned that the Nazis initially spared his paintings. He died in 1949, with Pechstein passing away six years later. That marked the end of the first generation’s search: Like so much else, the bridge across the Atlantic lay in ruins.

Second Generation

Hans Heymann, Jr., went on to become a successful American. “In contrast to his father, the war didn’t make him bitter,” says his daughter Kendra. “He was thankful for his new life.” As an economist, he analyzed the global situation for the CIA, advised three presidents on relations with Moscow and worked on the legendary Pentagon Papers, which addressed the American debacle in Vietnam.

It was only in 1979, once the Vietnam War had come to an end and America was once again at peace, that Heymann turned his attentions to his family’s history and relaunched the search. Like so many people, he dove into his family’s history at a moment when he himself was on the way to becoming history. With his retirement approaching, Heymann sensed that there was some unfinished business to take care of. So, he picked up the trail where his father had lost it 30 years before. He sat down at a typewriter and composed a letter to Germany. “I am writing to you now in the remote hope that you may have some additional knowledge of the fate of these pictures. Yours sincerely.”

The letter was addressed to Max K., the son of the painter, an engineer from Hamburg who was also struggling with the vast legacy his father had left behind. Max K. Pechstein was assembling an archive of his father’s works, collecting photographs, letters and art catalogs. Max K. answered the letter from America in German, because his English wasn’t up to the task. He said that he found himself in a similar situation as the Heymanns. “The chaos of war and destruction have also completely relieved us of earthly possessions."

The life works of his father, he wrote, had been scattered "to the four winds.” Much of it had made a reappearance on art markets, he wrote, but it was too late to demand that the property be returned. “Looking back,” Max K. wrote, “one finds oneself standing speechless before all of these injustices and one must repeatedly ward off rising fury.” In the following decades, the two families helped each other resist the temptation to give up. Their interests overlapped, with the Pechsteins collecting for their archive and the Heymanns searching for their collection – and their efforts complemented each other in that they were able to search on both continents. The bridge at this point was primarily a feminine one, with most of the impetus coming from women. Pechstein’s partner Leonie was energetic and could speak English, while Heymann’s wife Barbara was known for her vigor. “She had incredible amounts of energy,” says her daughter Kendra. When Barbara Heymann wasn’t focusing her attentions on her house in Washington or on her ice cream parlor in Puerto Rico, she collected all the information she could find about the scattered works of Max Pechstein. On one occasion, she obtained a list of all Pechstein drawings in the possession of the National Gallery of Art in Washington; on another, she acquired Pechstein letters from the Busch-Reisinger Museum near Boston.

She sent piles of art catalogs to Germany, and Max K. Pechstein’s heart raced every time the mailman rang the buzzer. Sometimes, the packages were so thick that Pechstein had to retrieve them from the customs office. Her work was a “gift from heaven,” and “a miracle,” he wrote her. At one point, he referred to her as “our wonderful American assistant.”

Increasingly, the two families became friends, sharing their hopes and disappointments – pertaining to both their search for the paintings and the state of the world. Pechstein at one point bemoaned the barbarity of the early-1990s arson attacks on refugee hostels in Germany, while Heymann wrote about the U.S. election night in which Bill Clinton won the presidency, to the delight of both.

The Heymanns’ collection remained lost, but there were enough small victories to maintain hope. Pechstein paintings from other collections would occasionally surface, or documents would show that drawings from Heymann’s own collection had been sold by a gallery in Zürich or shown by a gallery in Heidelberg. When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, Heymann hoped that the global thaw might release new signs of life from his artworks.

Before long, the 20th century drew to a close, with both families visited by illness increasingly often. In May 2005, Max K. Pechstein related that his second leg had now been amputated. One year later, shortly before their deaths, the Heymanns wrote with shaky handwriting how thankful they were for this friendship and for all the help. “Please remain as healthy and cheerful as you can. Many kisses and best wishes. Hans + Barbara.” They would be the last words of an intimate relationship. It ended in the knowledge that, while they didn’t reach their ultimate goal, they had found soulmates on the journey.

Third Generation

Kendra Sagoff lives in a home on the outskirts of the American capital, with old oaks outside and the Potomac flowing by beyond them. When visitors come, she heaps the coffee table with pastries and ice tea. Throughout her life, she has fought for justice and public welfare; she has worked as a defense attorney and fought for clean air at the Environmental Protection Agency. Now, Donald Trump is in the White House. “It becomes clear,” she says, “how rapidly norms and values can shift.”

Given the current situation, she says, she wonders if it is right to continue looking for old paintings or whether she should focus on the present instead – by helping young Latinos learn English, for example, to show that America still welcomes immigrants. Just as the Heymanns themselves were welcomed in 1936. “I wonder if I should become active on political issues instead of personal ones."

But then she sometimes gets the feeling that fate is encouraging her to keep going. Following the death of her parents, Kendra Sagoff contacted all the agencies that are still searching for the property of Jewish families. Her father Hans Heymann had filed a claim with the Holocaust Claims Processing Office (HCPO), a division of the Department of Financial Services for the state of New York. Despite being seen as a "cold case,” the Heymann file was pulled out of the archive in 2013 and assigned to a young employee, who approached the search with new energy. “She started the whole thing anew,” says Sagoff.

Even today, the agency in New York continues to receive countless inquiries from victims of the Nazis, showing just how many of the injustices still haven’t been cleared up. But even here, the Heymann-Pechstein story is seen as being particularly moving. “What is unusual in this particular case,” the agency wrote in an email, “is the close personal connection between the Heymann and Pechstein families, which has spanned three generations, and how tirelessly they have worked together over seven decades to find these works of art.”

The agency says what happened to the paintings “continues to remain a mystery. Whether or not they survived the war is unclear, but the HCPO will continue to diligently search for them,” the agency wrote. “The fact that several drawings from the collection have resurfaced on the art market throughout the years is certainly encouraging.” With the help of the internet and international databases, the HCPO managed to find, for example, a Max Liebermann pastel that once belonged to Hans Heymann. Kendra Sagoff accepted a settlement and a note was added to the auction catalog indicating that the work of art had belonged to her grandfather. It now reads: “Heymann Collection." It was the first success in 70 years.

Long ago, she made the decision not to measure the value of this endless search in the number of paintings she managed to find. She had a different approach after the death of her parents; she read their letters and felt deeply sorry for them. "They did so much work and didn’t find even a single Pechstein,” she says.

Sagoff has since realized that the search itself had been the goal. The collection was a bridge for her father as well, “a way of going back to the happy part of his childhood, where he lived with the paintings and they were an important part of his family’s life,” Sagoff says. “He especially remembered the painting ‘Der Tanz’ ('The Dance’). It hung in the Berlin apartment next to the grand piano and it was huge, and he loved the colorful, dancing women,” she continues. “My father’s search kept alive the memory of the paintings and of the Heymann family.”

Even though she has only been focusing on the paintings for the last five years, works of art that she has never seen or touched, they have acquired significant sentimental value for her. “This collection is so full of love,” Kendra Sagoff says, because it embodies so many things: The elder Hans Heymann’s love for his fallen brother; the younger Hans Heymann’s memories of his childhood; the intimate friendship between the Heymanns in America and the Pechsteins in Germany; and the link between the living and the dead, because one generation would take over the search from the last. “I find poetry helpful,” she says and quotes from a poem by Maurice Sagoff, her father-in-law.

The bridge called love

Unyielding stands;

Across it, life

And death touch hands.

Ultimately, she decided that this apparently tragic tale about lost paintings that have never reappeared is actually a happy story. “Even if I don’t find anything during my lifetime,” she says, “I won’t be disappointed.”

But she didn’t want it to be a solitary search, so she sought out the next generation on the German side. She learned that Julia, the granddaughter of the painter Max Pechstein, is now maintaining his archive. She sent her an e-mail with a photo of herself standing in her living room with the memento from her parents hanging on the wall behind her, the framed page from the calendar, “Fishing Port in Bornholm.”

Julia Pechstein from Hamburg replied with a photo of herself. She is standing in her own living room and pointing to a picture on the wall, exactly the same one that Kendra Sagoff has hanging in her home in America: “Fishing Port in Bornholm,” but it is the original, having always stayed in the family. Both women fell in love with exactly the same painting, independently of one another. When Kendra Sagoff looked at the photo at home in Washington, she felt a chill. Can such coincidences be real? “No,” she said to herself, “it must be some kind of cosmic sign that the connection goes on.”

Wasn’t that the declared aim of the artist group Die Brücke, after all, connecting one shore with another?

In her letter, Julia Pechstein wrote: “As you can see, we have the same taste. And the same goal, that of finding our grandfather’s paintings. It takes a lot of time. But one day, the search will succeed.”