Just a few minutes into the interview, Heinz-Christian Strache has already grown tired of answering questions. He might suspect that he has already said too much. He leans back on his wooden chair, his voice shaky. “Clearly, you’re only interested in one topic,” says the leader of the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), his eyes narrowing. His press officer slides his hand across the table to indicate that the subject is closed. The subject in question – Strache’s stint in the Neo-Nazi movement – is very sensitive indeed.

Up until this moment, the atmosphere is relaxed. In the wood-paneled lounge of a historic Innsbruck guesthouse, Strache speaks of his early youth. In traditional bottle-green Austrian garb, he sits calmly in his chair, bantering. The mood suddenly changes when he is asked about his Neo-Nazi past. For the 48-year-old Strache, who is poised to become vice-chancellor of the Austrian government following today’s parliamentary election, these questions are more than just unpleasant.

Ten years ago, there were revelations in the media, most of which were supported with photo evidence. At the time, the FPÖ leader was shaken, but not dethroned. SZ research now shows the extent of his involvement in the Neo-Nazi movement as a young man. According to eye witnesses, the findings of the German authorities, and archives, Strache was active in Neo-Nazi circles for years, and was still part of the movement when his FPÖ career began.

His line of defense during the Innsbruck interview resembles statements he has made in years past: he condemns national socialism and extremism of any kind. He refers to his years in the movement as a learning experience. “While trying to find myself, I took a close look at a lot of things,” Strache says, as he moves his index finger across the white table cloth. He doesn’t see this particular experience as a mistake, he says, and declines further comment. His press officer shakes his head and dismisses the phase as a harmless youthful transgression. He then warns that the interview will be cut short if any further questions are asked on the matter.

With this strategy, Strache successfully put the subject to rest in Austria when it first came up a decade ago. He has since become one of Europe’s most successful right-wing populist politicians. In 2016, he even made it onto the cover of Time Magazine. Over the past 12 years of his political career, his perpetual campaigning has turned the FPÖ into a people’s party, and the declared role model of the Alternative for Germany (AfD). In today’s parliamentary election, the FPÖ could get 25 percent or more of the popular vote. After Germany’s recent federal election, there was widespread outrage when the AfD got 13 percent of the vote and made it into the Bundestag. This outrage may in part be the result of the relative newness of the party. In Austria, hardly anyone has raised an eyebrow at the idea that the FPÖ could be part of the next government. The right-wing populists have been a fixture of day-to-day politics in the country for far too long. If elected, Strache would be the first politician with a Neo-Nazi past to be part of a European government.

Strache himself claims he was involved in the movement for three years. However, his biographers Claudia Reiterer and Nina Horaczek have written that he was active in far-right circles “from around 1985 to 1992”. In 2006, Heinz-Christian Strache stated that he had “stable political views” by the beginning of the 1990s. If his ideological position had formed by then, the previous years must have had a decisive influence. We have reconstructed Strache’s past in 11 chapters:

1. With the Wiking-Jugend in Fulda

Heinz-Christian Strache spent the final hours of 1989 in a German police bus with barred windows. He wasn’t allowed to leave until he was identified. It was cold, and the situation was humiliating: Strache began the new decade behind bars.

The 20-year-old from Vienna had travelled more than 800 kiliometers by train from his hometown to Fulda, Germany. His girlfriend and a few other Austrians tagged along as well. From Fulda, the group travelled east by car to Simmershausen on the East German border, where a few like-minded youths were waiting for them – along with dozens of counter-demonstrators. The German Wiking-Jugend had come to hold its annual New Year’s Eve march, just as it had done for years. The organization is modelled on the Hitler-Jugend, and the German Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution has classified the group as Neo-Nazi. In 1994, it was made illegal.

Around 8 p.m. Strache and his companions marched to the East German border, which was still secured.

“We are on your side,” the group assured the West German authorities. “They presented themselves as the saviors of Germany,” says the man who was the head officer at the time. By this point at the very latest, the Austrians must have realized that the Wiking-Jugend event was against the law – just as it had been in previous years.

SZ

"At a meeting place that was kept secret until the very last minute – a quarry – about 20 people lit torches, sang songs, chanted, and marched toward the inner German border,” according to a statement of the Hessian Office for the Protection of the Constitution. Strache also held a torch, and the group sang: "Deutschland, Deutschland über alles, über alles in der Welt” – the first verse of the German national anthem that was used until 1945, and which declared Austria and Denmark part of the Reich. The Fuldaer Zeitung wrote of horns that “floundered rather than flourished“. The text also mentions a “rune cross” – which possibly hinted to the Austrian Neo-Nazi group “Volkstreue Außerparlamentarische Opposition” (VAPO). Today, the former Fuldaer Zeitung journalist suspects that the Wiking-Jugend wanted to stage an event for the media on that fateful New Year’s Eve. The Hessian Office for the Protection of the Constitution writes that four stun guns and one gas pistol were seized among the people arrested that night.

“The Wiking-Jugend invited us to protest the wall, and I was always completely against communism,“ Strache says in Innsbruck. He claims he didn’t know what he was getting himself into: he researched the organization afterwards and decided that he would no longer attend such events.

In interviews with other journalists, Strache has claimed that the Wiking-Jugend march he attended was meant to be a humanitarian act:he and his friends had thrown "bread baskets” across the inner German border. Eyewitnesses that the SZ spoke to were unable to confirm this. In its propaganda magazine entitled Wikinger, the Wiking-Jugend describes the “New Year’s event at the zonal border”, and there is no mention of bread baskets or anything of the sort. However, the article does mention the comrades who were arrested and spent their New Year’s Eve in the police bus. The Wiking-Jugend counted all of those arrested, among them the Austrians, to their group, as did the police and the Office for the Protection of the Constitution.

2. Camping with the “Volkstreuen Jugend”

There is much to suggest that Strache was in touch with the Wiking-Jugend long before the Fulda incident. In the second half of the 1980s, he attended a camp in Carinthia, which he claims was organized by the “Familienkreis Volkstreue Jugend”. Strache says he didn’t think the camp was radical. It is not clear who is behind the “Familienkreis Volkstreue Jugend”. Experts are not familiar with any organization that goes by that name. However, the Wiking-Jugend also refers to itself as the “Volkstreue Jugend”, as many of the group’s publications show.

In his interview with the SZ, Strache admits for the first time that the camps he attended in Carinthia were linked to the Neo-Nazi organization. “The Volkstreue Jugend was also in contact with the Wiking-Jugend,” While the FPÖ leader does not name names, he does say that he found out about the Fulda event at the camp.

3. Joining the German nationalist fraternity

Even much earlier on, Strache was in an environment that would have a significant impact on his political views. At 17, through a friend he met at a Kung-Fu class, Strache joined the Vandalia fraternity in Vienna. He was thrilled with the organization and quickly became a full member, forming a lifelong affiliation. He presented the fraternity’s ideology to newcomers, became a fencer and engaged in traditional duals. The inside of the Vandalia fraternity house in 2013 can be seen in previously unpublished photographs that the SZ has gained access to.

SZ

One of the photos depicts a steal helmet with a scull on top of it. Others show young men with gaping wounds from fencing. A black, white, and red Imperial War Flag from the German Reich is hanging on the wall. It is a flag that Neo-Nazis often wave at their marches. The Vandalia fraternity is clearly of the German nationalist persuasion.

Through the nationalist group, Strache also met the well-known right-wing extremist Norbert Burger and fell in love with his daughter Gudrun. Later on, she travelled with Strache to Fulda.

4. An uproar at the Burgtheater

Strache had his first major public appearance on November 4, 1988. Still unknown at the time, he appeared on television as an angry heckler at Vienna’s Burgtheater. That evening, the writer Thomas Bernhard was celebrating the premiere of his play “Heldenplatz,” which was critical of the way Austria was addressing the National Socialist era. Strache was a gawky young man with a preppy haircut at the time, but he is easily recognized in the video. He stood in the gallery brandishing his fist and shouting angrily at the stage with other young men. Bernhard supporters on the floor shouted “Nazi Scum” back at them. Later, newspapers wrote that a handful of “right-wing extremists” had managed to get tickets to the show.

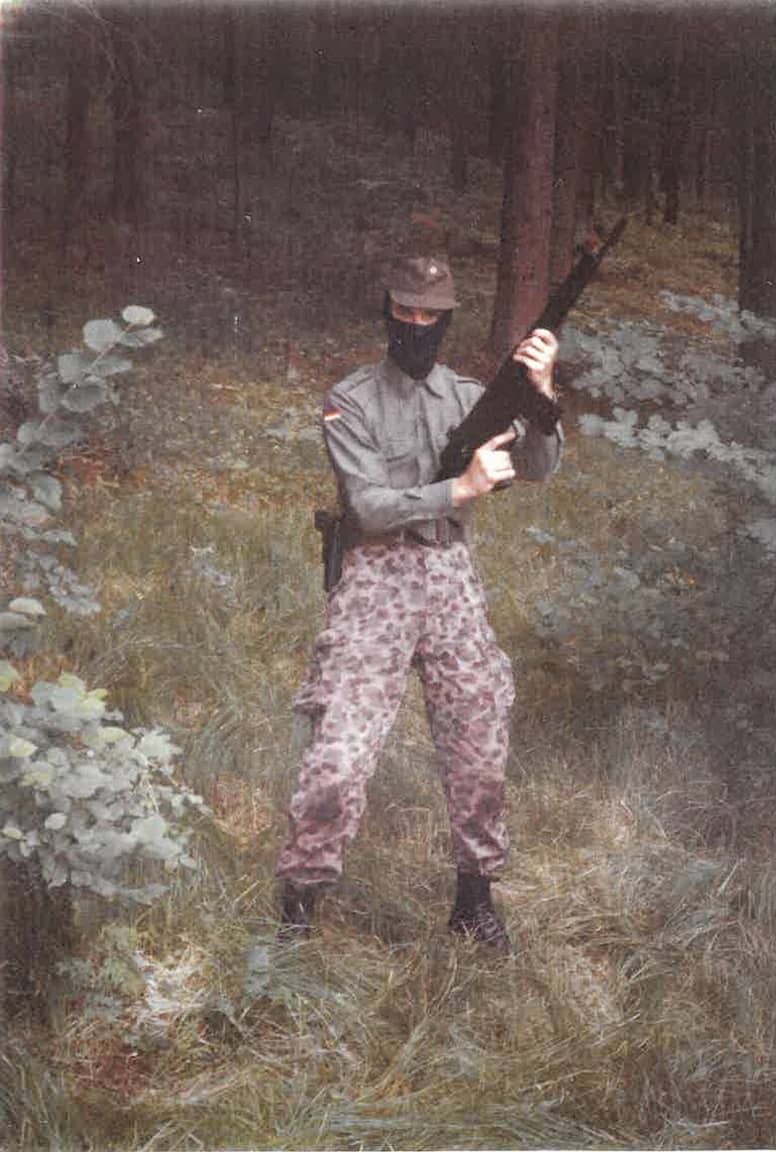

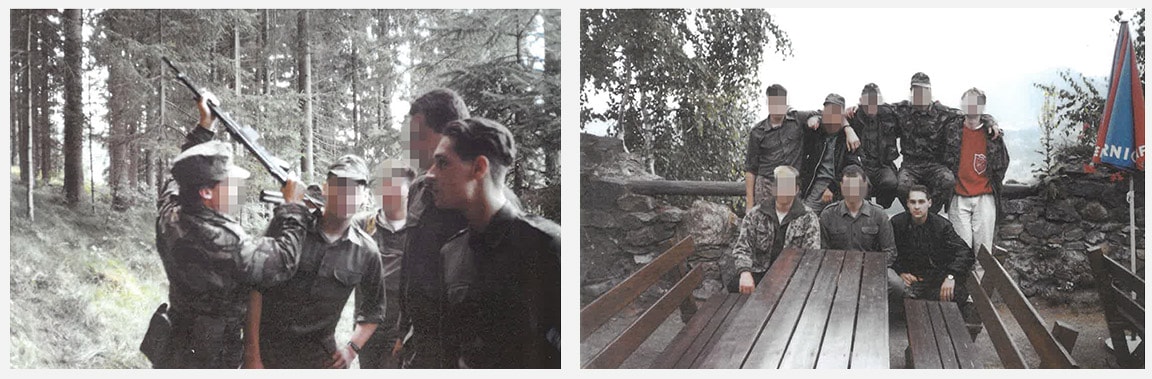

5. War games in the woods

Around the same time, Strache began practicing a new hobby: with his friends from the fraternity, he shot soft guns in a wooded area in Carinthia, dressed in full battle gear. The replicas of weapons that fired plastic projectiles and paint balls were popular at the time, especially among young men. But the games had a “political” character, as one person who took part describes. Notorious Neo-Nazis crawled through the undergrowth with the future FPÖ leader, among them Andreas Thierry, who later went on to become a member of the far-right, ultranationalist National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD).

Archiv Horaczek

One of the photos depicts a steal helmet with a scull on top of it. Others show young men with gaping wounds from fencing. A black, white, and red Imperial War Flag from the German Reich is hanging on the wall. It is a flag that Neo-Nazis often wave at their marches. The Vandalia fraternity is clearly of the German nationalist persuasion.

Through the nationalist group, Strache also met the well-known right-wing extremist Norbert Burger and fell in love with his daughter Gudrun. Later on, she travelled with Strache to Fulda.

4. An uproar at the Burgtheater

Strache had his first major public appearance on November 4, 1988. Still unknown at the time, he appeared on television as an angry heckler at Vienna’s Burgtheater. That evening, the writer Thomas Bernhard was celebrating the premiere of his play “Heldenplatz,” which was critical of the way Austria was addressing the National Socialist era. Strache was a gawky young man with a preppy haircut at the time, but he is easily recognized in the video. He stood in the gallery brandishing his fist and shouting angrily at the stage with other young men. Bernhard supporters on the floor shouted “Nazi Scum” back at them. Later, newspapers wrote that a handful of “right-wing extremists” had managed to get tickets to the show.

5. War games in the woods

Around the same time, Strache began practicing a new hobby: with his friends from the fraternity, he shot soft guns in a wooded area in Carinthia, dressed in full battle gear. The replicas of weapons that fired plastic projectiles and paint balls were popular at the time, especially among young men. But the games had a “political” character, as one person who took part describes. Notorious Neo-Nazis crawled through the undergrowth with the future FPÖ leader, among them Andreas Thierry, who later went on to become a member of the far-right, ultranationalist National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD).

Pictures were taken at the event, some of which were published in 2007. They showed Strache posing with a weapon, learning how to use a baton, and standing next to a war memorial. German authorities refer to such activities as “paramilitary sport”. Neo-Nazis see these types as activities as “preparation for the ‘Hour Zero’ they strive for, in which they will act as an ‘Avant Garde’ that aims to build a new national socialist system,” writes the North Rhine Westphalia Office for the Protection of the Constitution. Strache’s

war game buddies appear to share these views. Two of them were once associated with VAPO, a fascist group led by the Holocaust denier Gottfried Küssel, who is currently serving a prison sentence for national socialist crimes.

While Strache later described the exercises as harmless games of paintball, VAPO relied explicitly on such games at the time. In the September 1990 issue of the Neo-Nazi magazine W – Die Neue Front, Küssel’s group reported on “a military-like exercise with comrades from Vienna and Lower Austria”. The use of “paint ball guns helps achieve the most realistic situation possible,” the Neo-Nazi magazine wrote, with VAPO lettering and a rune cross beneath the text.

Between 1987 and 1992, Küssel organized paramilitary exercises close to Langenlois in Lower Austria. While Strache was here at least once as well, he claims to have left early because he was appalled by the conditions and the people he found there. He asserts that he went out of curiosity.

However, two former Neo-Nazis who at the time practiced the accession to power on a regular basis with Küssel told the SZ that the paramilitary exercises were reserved for insiders, for members of a “closed circle”. They asserted that popping in as a guest was impossible. “There were no invitations without a recommendation from an important member,” they said.

According to the two dropouts, the Küssel group’s program was extensive: the men-only group learned how to behave at an interrogation, received baton training, and took part in ideology seminars. At times, they also practiced shooting with live ammunition. The Documentation Center of Austrian Resistance (DÖW), the country’s biggest center for right-wing extremism, states that these claims reflect the facts.

The two former Neo-Nazis also spoke of the “Don’t buy from Jews” stickers that were circulating at the time. Razor blades were fixed to their backs to injure people who attempted to remove them.

Archiv Horaczek

6. At the DVU in Passau

In 1990, German police temporarily arrested Strache once again. On March 10 of that year, he attended an event in Passau entitled “Reunification Now”. It was organized by the German People’s Union (DVU), which later merged with the NPD. The audience sang all three verses of the German national anthem, and one attendee held up a sign that said “Upper Schlesia is and remains German”. As archival photos and reports from the party’s own newspaper show, someone hung an Imperial War Flag at the front under the speaker’s podium. The Holocaust denier David Irving was scheduled to give a speech at the Nibelungenhalle, but the German authorities barred him from speaking. A year earlier, Strache had attended a talk that Irving was meant to give in Vienna, which the authorities also banned. Instead, an FPÖ politician talked about “Austria’s German commitment.“

The Bavarian Office for the Protection of the Constitution has classified the DVU’s views as “primarily nationalistic xenophobia, which is occasionally characterized by a mix of anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism.” Moreover, the DVU has attempted to “minimize or justify” the role of Hitler Germany in the Second World War. The German Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution noted that around 4000 people came to Passau, 11 of whom were arrested. At the time, they were accused of “carrying illegal objects,” as the SZ wrote. Strache was among those arrested. He was accused of carrying a stun gun.

7. A double life

While Strache was still involved in the Neo-Nazi movement, he joined the FPÖ in 1989. As an only child who grew up without a father, some of his party friends have said the FPÖ was almost like a family for him. The 20-year-old liked the course that party leader Jörg Haider had taken. A short time before Strache joined the party, the Carinthian state politician had declared Austria an “ideological freak”, thus appealing to voters on the far right.

Strache, who worked as a dental technician at the time, was invited to join the party by Herbert Günther, an FPÖ member. The dentist was also member of a right-wing fraternity, and he knew that Strache was in a relationship with the daughter of the right-wing extremist Norbert Burger. However, Günther told the SZ he had no idea that Strache had ties to Neo-Nazis like Küssel. When pictures of Strache’s paramilitary games and ties to the Wiking-Jugend were made public in 2007, Günther was unpleasantly surprised: “These things were incompatible with the young man I knew at the time.“

While Strache was attending war-like, right-wing extremist events, he was also presenting himself to his party friends as a polite, reliable, and grateful young man. Günther, at the time the FPÖ leader in Strache’s home district of Landstraße in Vienna, saw him as a political talent and supported his rise. Both men were critical of the dominance of the SPÖ and ÖVP, Austria’s two major parties. Strache’s acquaintance with Günther may well be the reason why he decided to dissociate himself from the Neo-Nazi movement.

8. On the far right of the FPÖ

At first, Strache was too far to the right for some of his FPÖ colleagues, as former party members said of meetings in Vienna. From 1990 to 1994, long after Strache had joined the party, Strache also tried to join the FPÖ’s youth wing, the Ring Freiheitlicher Jugend (RFJ), but was rejected. “Strache and others wanted to take over the organization to turn it into an ideological think tank,“ says Peter Westenhaler today. At the time, Westenhaler sat on the RFJ board and can recall arguments with the young politician. His RFJ colleague Herbert Schreibner, who later went on to become Austria’s defense minister, says: "Strache was too right-wing for us at the time, and he made too much of a racket.”

Even party friends who saw themselves as far right have said similar things about Strache. In 2008, the late FPÖ veteran Otto Scrinzi said in the ”HC Strache” biography: "I think Strache is a nationalist through and through. Maybe he was even a little too far to the right as a young man.” Prior to 1945, Scrinzi was a storm trooper for the Austrian SA, and he worked at a Nazi institute in Innsbruck.

Screenshot SZ

9. “I was never a Neo-Nazi“

After Jörg Haider and his supporters left the FPÖ in 2005, the party was in shambles. Heinz-Christian Strache was then appointed its leader. Part of his work to rebuild the party included an interview book in which he was asked about his life. While he did not mention his time in the Neo-Nazi movement, Strache’s past caught up to him a short time later. Pictures of the alleged war games were published in 2007. The Austrian press also printed a picture in which Strache can be seen in the fraternity house elevator, apparently making a three-finger salute known as the neo-Nazi Kühnen salute – a gesture that is illegal in Germany. Strache asserts that he was just ordering three beers. On camera, the FPÖ chairman says: "I was never a Neo-Nazi and I am not a Neo-Nazi.

10. Absolved by the Chancellor

Both the Austrian public and other politicians were indignant – but they quickly calmed down. This was in large part thanks to the former SPÖ Chancellor Alfred Gusenbauer’s sense of compassion: he was not about to hold a lifelong grudge for anyone’s “youthful folly”, he said. Strache was absolved of any wrongdoing by the country’s highest social democrat, putting an end to any debate about his resignation.

In Germany, such revelations would mean the end of a political career. But in Austria, Strache is increasingly successful – even though his party has come under fire for how far to the right it has gone. Regardless of people’s position on the political spectrum, the view that no one cares anymore is widespread in Austria.

In this election campaign, neither the media nor the political competition have addressed Strache’s years in the Neo-Nazi movement. Both Sebastian Kurz of the Christian-democratic Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) and Christian Kern of the Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ) have not ruled out the possibility of a coalition with the FPÖ. Since the grand coalition of recent years has failed repeatedly, the major parties may be taking a pragmatic approach. In mathematical terms, apart from an alliance with the FPÖ, no other coalition is possible.

11. Remorseful only to his mother

Strache has only been so successful in covering up his past because he is the only person who can answer many of the questions. The FPÖ leader either prefers to keep some of the details to himself, or he threatens to walk out of interviews, as he does during the SZ interview in Innsbruck. Once the questions of the 1980s abate, Strache leans back in his chair in the wood-paneled lounge and starts chatting again.

But a lot remains unclear: who were the men with whom he shouted from the gallery at the Burgtheater? How did he end up at Küssel’s paramilitary events? Apparently, Strache only showed remorse to his mother, who declined to speak with the SZ. However, in 2007, when the first facts were published, Marion Strache said to the Kurier newspaper that both she and her son cried: “He is no longer the same person he once was,” she said. “Deep down, he regrets it“.