Johann Scheerer and Omar Rodríguez-López on pain

„Life and happiness need destruction“

How does suffering affect life and art? Can it be turned into something positiv? Into confidence? Author Johann Scheerer and „Mars Volta“-Guitarist Omar Rodríguez-López on the topic.

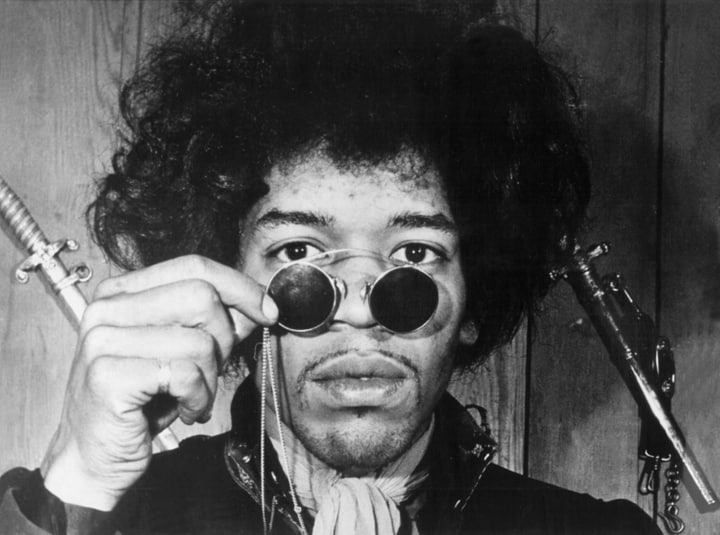

The musicians Johann Scheerer and Omar Rodríguez-López share a long history of friendship and artistic collaboration. Rodríguez-López, mastermind behind bands such as At the Drive-In and The Mars Volta and one of today’s most radical contemporary alternative-artists, recorded „The Clouds Hill Tapes Pt. I, II, & III“ in Scheerer’s recording studio in Hamburg. By the end of April, they’ll be releasing the complete works of The Mars Volta in the LP-Box „La Realidad De Los Sueños“ – „the reality of dreams“.

But the connection between them runs deeper, as they both had their share of pain. „Only two of my high school friends are still alive“, Rodríguez-López recently said in an interview. At the age of 17, he slept rough for about a year, having escaped an abusive childhood home. Scheerer has adressed the kidnapping of his father, Jan Philipp Reemtsma, in two bestselling books: an autobiography, „Wir sind dann wohl mal die Angehörigen“ and the semi-fictional „Unheimlich nah“.

SZ: Mr. Scheerer, Mr. Rodríguez-López, if pain does actually effect life and art …

Johann Scheerer: … my opinion might change in the course of our conversation, but this is how I see it now: This whole idea that pain might be a driving force for art is just bullshit. A horrible cliché. The whole theme of art somehow getting better or deeper through pain is a myth made up by the entertainment industry. Nothing good comes from pain. And whenever an artist says: „I have suffered in life, and it made me the person I am now“, that is a glorification. It’s never because of the pain, it’s despite the pain. I think, if any of us – and by „us“, I mean you, Omar, myself and all the other artists that went through difficult phases in their lives – would be way better off if we hadn’t gone through any pain. I think pain is just destructive. End of story. It’s got nothing to do with creativity. Same goes for poverty.

Do you agree, Mr. Rodríguez-López?

Omar Rodríguez-López: Throughout history, there have been many examples, some of them our greatest artists, that particularly proove your last point – which is: They actually came from money. They had all the opportunities to learn and to study – whether we’re talking about Salvador Dalí or William S. Burroughs. At the same time, those artists or any other examples that we could come up with, were in fact struggling: Burroughs, obviously, with his homosexuality. Dalí with the fact that he felt like he didn’t fit into his family’s circles. So, I have to disagree: Pain is driving everything. It is a fundamental truth about art and creativity that there’s nothing without pain. Or to be more precise: There’s nothing without destruction.

You’ll have to explain that.

Rodríguez-López: Johann said that pain is just destruction and thus not creative. I would argue the exact opposite, using the exact same words. Pain is destruction and destruction is the only way to develop. That is true for art and for every aspect of society. Even for constructing society itself.

Constructing societies is destruction?

Rodríguez-López: It’s nothing but a massive act of destruction. We’re able to trace the origin of man only by looking at how much we destroyed. Tracing the path of homo sapiens is synonymous with animals disappearing, trees disappearing. This results in conflict. And conflict is what moves us forward.

Scheerer: What you’re saying is: Conflicts force us to find solutions – and therefore bring development?

Rodríguez-López: Yes. To go way back: Human beings were part of the animal kingdom – they were part of the food chain. That’s the conflict. Solution: We violently put ourselves on the very top of the food chain. Then new conflicts arose: lack of space, distribution battles. Therefore we had to construct laws. But the origin of all of all that is destruction. It’s the same with writing a song.

What gets destroyed while writing a song?

Rodríguez-López: You’re destroying all the possible ways in which it may have developed. You’re erasing all the different chords, intervals, melodies and arrangements in order to see a manifestation of your own view – which is the same as taking control of destruction and turning it into creativity. You’re cooperating with destruction. When im starting off with a song, I can hear hundreds of different versions and I love each and every one of them. They all make me happy. But I have to choose one that’s going to be mixed, mastered and printed.

Scheerer: That and an acoustic version.

Rodríguez-López: That is why I don’t ever listen to my records. They remind me of all those other versions that never came into existence.

Could you give us an example?

Rodríguez-López: Our single „The Widow“, the one that brought The Mars Volta into the mainstream. The original version was just an acoustic guitar and a voice – and it sounded beautiful. It sounded perfect. We captured lightning in a bottle. So I was terrified to add anything.

What happened?

Rodríguez-López: I battled through the fear. One day I said: „Maybe a maraca comes in right here.“ And that was it. For a long time it was acoustic guitar, voice and maraca. Then later I was like: „Oh, maybe some percussion might help in the bridge.“ And it was that. And later it was like: „Maybe, just maybe: some bass.“ In the end we had slide guitars, electronics, all these people yelling in the background – and a hit single. And all that just because I was willing to destroy what had seemingly been perfect. And because I had the time to do it. Deadlines destroy that process.

Scheerer: Tony Visconti, the producer who worked on David Bowie’s „Space Oddity“ and „The Man Who Sold The World“, once said: „We all know, the perfect time to mix a record is half a year after it’s been released.“

Rodríguez-López: Damn right!

You, Mr. Rodríguez-López, dissolved your band At the Drive-In, the year it got successful. You, Mr. Scheerer, built a huge recording studio while the music industry was crashing. By the time it paid commercially, you decided to write books. Is there less fear of making the wrong decision once you have gone through a lot of stuff? Is there more bravery or courage?

Rodríguez-López: I’d be cautious using the word bravery, simply because I think that’s something you can only see in retrospect. I broke up with At the Drive-in because I no longer believed in what we were doing. I felt spiritually bankrupt and couldn’t go on like that. So that wasn’t bravery. That was survival.

Scheerer: I’m completely with you on that. When I was working on my second book, I just didn’t know the core of the story for a long time. I was about halfway through it and I literally couldn’t tell what it was about. At one point I added one sentence, one single sentence, that became a chapter – and that changed the entire perspective. I realized I was aiming for a semi-fictional book. That this was the story I wanted to write – had to write. Though people were trying to convince me otherwise. But making that decision didn’t feel like bravery for a single second. In fact, I was feeling totally lost and scared most of the time.

Does „confidence“ sound better to you?

Rodríguez-López: Better, yeah. Though it’s more of an invisible confidence.

Where does that come from?

Scheerer: I’d say it comes from the certainty of death – ironic as it might sound. Bottom line: It doesn’t change anything. It doesn’t make any sense anyway. So why not do it?!

Rodríguez-López: To me, there’s another aspect to that confidence: the voices in my head. If I thought those voices were purely me, if I thought it was me telling myself things and me thinking things and me desiring things, I would not be confident. I would second-guess myself all the time. But the voices have nothing to do with me. I can completely trust them. When the voices say: „Shut the fuck up! This is what you’ve got to do!“, I’m going to do exactly that. I’m very good at following orders.

Scheerer: When someone asked Michelangelo: „How do you make a lion out of a stone?“, he supposedly answered: „Throw everything away that doesn’t look like a lion.“ Same goes for writing a book or making a record: You creat it by simply creating it.

Sounds like you don’t believe in writer’s block?

Scheerer: I know what it’s supposed to mean. And of course I have times when I don’t come up with great ideas. But what do you have to do to get over writer’s block? What’s the only thing you can do? Exactly: Write!

Rodríguez-López: Writer’s block is just a lame excuse for lazy artists.

Scheerer: I’d like to return to the topic of pain. There’s an aspect we have forgotten.

Which one?

Scheerer: At least in my experience, whenever we’re talking about pain, there are other people involved. And I just feel weird giving credit to the pain and therefore the people that made me or my family suffer. Because then we have a whole different story. One about becoming a victim. Giving credit to the pain means giving credit to somebody who made you a victim. And I don’t accept that. It was me who got through it. None of the pain pushed me forward. Most definitely not some individual that caused the pain.

Rodríguez-López: Maybe it’s just an issue of how we see pain as two very separate things. I see pain as a sentient, living, breathing energy in the universe that exists and has its own desires. It is not good and it is not bad. Those are just our moral categories. But pain exists and grows with or without us. That’s why the person who inflicts pain on us doesn’t even come into the argument in my mind. He or she is just the vehicle for the pain.

You’re speaking from personal experience here, aren’t you?

Rodríguez-López: I’m a survivor of sexual abuse. But I’ve never considered myself a victim of sexual abuse. There’s a person who did horrible things to me. But I understood – from a very young age – that he „learned“ this behavior from someone else. As I found out: His father had sexually abused him as well. It’s the transmission of energy throughout time and space. And in that sense, pain does deserve some of the credit, just like anything else that’s already there without us. It’s the way nature works, without caring whether it’s positive or negative.

Scheerer: Pain is in everything?

Rodríguez-López: Everything needs its opposite in order to exist. Daoism. You can’t have night without day, you can have dark without lights. Life and happiness need destruction.

Scheerer: That’s a pretty radical view.

Rodríguez-López: Pure nature. A sperm needs to penetrate an egg in order to create. It needs to be violent. A child needs to rip their mother open in order to come out and be born. Destruction is a part of life. That’s not a controversial opinion of mine. That’s just the hard, cold truth of it. The only true cliché is regretting having felt that pain. The feeling of: „We could have done something better to prevent it.“ No! That destruction, that pain is exactly what we needed at that moment in time to turn us into different people. Better people.

Scheerer: But the main question is: How do we respond to the pain? What do we do with it?

Rodríguez-López: I agree. But the pain itself is beyond our control. We can only control what comes after. My mother dying suddenly from a cerebral hemorrhage, having been completely healthy, at a young age: That’s beyond my control. But the pain of losing my mother shaped my life profoundly and has made me a much better person, a much better husband, a much better son, a much better friend, a much better artist because of what I did with that pain. There is nothing that can be given context without destruction. People only become real once they are destroyed.

Your mother became real to you through her suffering?

Rodríguez-López: Of course. I know who my mother truly was from witnessing her destruction. I can tell who she really was from having witnessed the suffering while she deteriorated during the last year of her life. She could hardly use her body, she could barely eat or communicate, but she would always find a way to ask me: Have you eaten yet? How is everybody? To return to the inital point of this conversation: That’s why we have art. Gertrude Stein used to say that art is the antidote to pain.

Scheerer: But isn’t it a horrible cliché nonetheless, if someone says they can only write when they’re in pain?

Rodríguez-López: Without a doubt! Mainly because it’s just ridiculous. If gratitude doesn’t inspire you, if life doesn’t inspire you, if a sunrise doesn’t inspire you, if seeing things flourish and prosper doesn’t inspire you, if black liberation doesn’t inspire you, if the LGBTQ-movement and all these things that are moving forward and are actually being created don’t inspire you – new ideas, new technology, if waking up in the morning realising you’ve still got both your eyes and ears and legs and arms: If that shit doesn’t inspire you, then, yeah, you’re kind of just going in circles. And I also think that you’re doing an injustice to real pain. You’re belittling it.

Pain has the tendency to turn into hatred. How do you manage not to hate?

Scheerer: If you give yourself over to hate, if you go down that path, that’s when you give power to the person who brought the pain. That’s when you turn yourself into a victim. That’s a thought, that helps me a lot. If you hate something profoundly, you’re chained to it forever.

Rodríguez-López: I’m comforted by the certainty that pain exists with or without us. If I hated the person causing the pain, it would be like hating sunshine or hating oxygen. Too bad, because: there it is. Besides: Who in this world hasn’t made a mistake that hurt someone else profoundly? Who in this world hasn’t passed a misguided judgment? Who in this world hasn’t done something they knew was wrong and regretted it later? I would love to meet all those perfect people that supposedly exist in the world.

Scheerer: I wouldn’t.