As Jack Terry descends the stone stairs into the Valley of Death, the quiet singing of birds can be heard from the nearby forest – an innocent, peaceful warbling.

Back then, though, Terry said when telling his story just a few hours earlier, he never heard the chirping of birds. Back then, he believes, the stench of death kept the birds away.

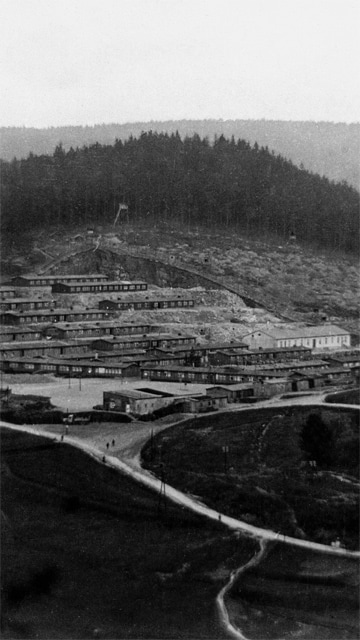

Between 1938 and 1945, at least 30,000 people died in the Flossenbürg concentration camp and its satellite camps. They were hanged, shot and starved to death – they suffered wretched endings.

Jack Terry, too, was not supposed to survive the Nazi terror. Just like his mother, his father and his three siblings, he was to be exterminated by the German killing machine. But the Jewish boy from the Polish town of Belzyce survived. And just like the chirping of the birds, he returned to the site of his suffering.

Hatred of Jews "is a virus that has been around since Biblical times."

The 89-year-old says that, though he left Flossenbürg in 1945, Flossenbürg has never left him. And Jack Terry has been visiting the place regularly since 1995, flying from New York to Germany to warn against the unthinkable: a repeat of what he, his family and millions of Jews were made to suffer. A repeat of the Holocaust. "Hatred of the Jews is the oldest hatred," he says. "It is a virus that has been around since Biblical times."

Terry is a short man with an upright posture, firm handshake and wiry frame. He is a proud American and a former soldier. And he is a man who will look you deep in the eyes as he tells the story of a German who shot 30 children, one after the other. His memories of the Nazi atrocities are as sharp as ever.

As is his critique of the current political situation in Germany. "I'm pissed off," he says, in reference to the burgeoning anti-Semitism in Germany and elsewhere in Europe. German foreign policy, he says, is far too accommodating of Iran, a country that "has dedicated itself to the destruction of Israel." In Europe, right-wing parties are on the rise and in Germany, the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany party, which refers to the Nazi period as but a "bird dropping" on 1,000 years of German history, has deputies in all state parliaments and in the federal parliament in Berlin. And that infuriates Terry, who has direct personal experience with the crimes of the Nazis. He is concerned that humanity hasn't fully learned the lessons of places like the concentration camp at Flossenbürg.

Flossenbürg Concentration Camp Memoria

In Flossenbürg, the Nazis robbed around 100,000 people of their freedom, their dignity and their humanity. In August 1944, a 14-year-old boy named Jakub Szabmacher was also locked away in the camp in northern Bavaria. Today, that boy goes by the name of Jack Terry.

His first experiences with anti-Semitism came well before the Germans invaded Poland in 1939. In his hometown, he was insulted as a "despicable Jew" and was constantly at risk of getting beaten up. But he first became acquainted with exterminatory anti-Semitism under the reign of the Nazis. They set up a Jewish ghetto in his hometown.

Jack Terry was nine years old when the war began. Early on, he viewed the German soldiers through a lens of childlike curiosity, polishing their boots and washing their cars. As a reward, he would be given brick-shaped loaves of bread. "It made me proud to bring the bread home," he recalls. But soon the boy was to experience the pain of the Nazi terror.

AFP

His father was shipped off to the Majdanek extermination camp and died in 1942. And when the Nazis cleared the Belzyce ghetto, Terry only barely escaped deportation to an extermination camp himself. As soldiers were herding the ghetto residents toward the train station, the boy fled into the forest on the search for his family. Back in the city, he found the body of his brother, who had been shot to death.

The Nazis also took away his mother and sister, with whom he was deported to the labor camp of Budzyn in 1943. There, it was up to SS Scharführer Reinhold Feix who would be allowed to live and who had to die. He separated newcomers into three groups: children, women and men. The children, about 30 of them, lay on the ground, Terry says. Feix pointed his weapon at them – as he tells the story, Terry forms his thumb and index finger into the shape of a pistol, his gaze fixed on his counterpart. "He shot them all," Terry says, making shooting motions with his hand.

"My life was over. I was no longer myself."

But Jakub was able to escape the group of children, crawling unnoticed to the men who had been selected as being "fit to work." He stood on two rocks to make himself look taller – and once again, he had barely escaped death. After the men were taken away, he learned that Feix had shot his sister in front of his mother – and then murdered his mother as well.

Even today, the pain Terry feels is beyond words, his eyes filled with disgust and grief. His voice cracks and he coughs as he wipes the tears from his eyes with a white handkerchief. After a brief moment, he continues speaking. It was May 3, 1943. "My life was over," he says. "I was no longer myself."

In August 1944, the Nazis transferred him and others to Flossenbürg, where he was given the prisoner number 14086, a fact which is also documented in the museum now at the memorial site. For days, the newcomers were kept naked, given an extremely degrading examination by the camp doctor and marked with a number on their foreheads. The number indicated the prisoner's ability to work, as determined by camp personnel. On Terry's forehead, they scrawled a 2, and he was sent to the nearby rock quarry.

As the American troops advanced closer and closer in spring 1945, the Germans disbanded the Flossenbürg concentration camp. They made plans for the camp's "evacuation" and in April, they forced the more than 40,000 prisoners in Flossenbürg and its satellite camps to begin marching to the south on foot. Many died on the Death March.

Again, though, Jack Terry was lucky. One day before the march was to begin, a fellow prisoner warned him not to return to the barracks. Instead, he was told to go to the basement of the laundry building abutting the roll call grounds. There, another prisoner hid him in a tunnel full of pipes leading to the kitchen, a narrow duct full of heating pipes. Terry no longer knows how long he spent hiding in the tight, steamy, underground hole, but thinks it was perhaps two days. "I thought I was going to die," he says. He then sought shelter in the typhoid section of the hospital barracks until the Americans liberated the camp on April 23.

"The day of liberation was the saddest day of my life."

When the Americans liberated Flossenbürg, 15-year-old Jakub Szabmacher was the youngest of the 500 prisoners who had been left behind. The American soldiers gave him food and chocolate – and humanity. Everything that the Nazis had taken from him. And yet, Terry says, "the day of liberation was the saddest day of my life." For the first time, it became clear to him that he had nobody left. He was the only member of his family to survive. "I had no country. I had no language. I had nothing at all."

An American soldier took him back to the U.S., where he was adopted by the Terry family. He learned the language and learned to read and write. "They treated me like a human being," Terry says. He worked hard to pass the entrance examination for Brooklyn Technical High School. "I really wanted to become an American." He passed the test and went on to become a geologist.

Privat

In 1955, he returned to Germany temporarily as a U.S. soldier and at one point, his duties even led him back to the quarry at Flossenbürg – back to the place where the Nazis had robbed him of his childhood. A German geologist told him: "There used to be a concentration camp down there. But it wasn't so bad." The sentence became burned into Terry's memory. Sixty years later, he can still quote it word-for-word. In German.

Despite the encounter with his past, Terry remained silent about the horrors he had experienced there. He started a family and didn't even talk about it with his wife. Years passed before he was able to confront his own history.

But then, in the forests of Venezuela, he suddenly had a vision:

Sebastian Beck

The roll call grounds at Flossenbürg appeared before him, a dying man lying on the ground. The "walking corpse," as Terry calls him, had a piece of bread in his hand. Other prisoners rush him, trying to take his bread from him. "How is it possible for human beings to become so debased?" Terry began wondering. The forest vision triggered within Terry a need to understand what had happened to him. So, he became a psychiatrist.

When Terry returned to the site of his agony for the first time in decades in 1995, he felt lost. Grass covered the site of the former concentration camp and there was a factory hall on the roll call grounds. There was no sign of the wooden prisoner barracks on the hillside, with family homes now extending far inside the former camp boundaries. Terry could hardly recognize the place and was afraid that the crimes of the Nazis could be forgotten. It is only because of the efforts of Jörg Skriebeleit, who was still a university student in 1995 but who leads the memorial site today, that Terry has continued coming back.

Skriebeleit dedicated himself to documenting the Nazi period in Flossenbürg and the camp was restored. In 2007, the museum exhibition was finally opened, ultimately being honored as a European Museum of the Year in 2014.

For how long must he continue speaking of the murder of his mother and sister?

Skriebeleit says that Terry doesn't want to become the "face of Flossenbürg." Still, he says, the American is an "important role model" for the memorial site and a personal friend. "But he won't allow anyone to misrepresent him," Skriebeleit says. And a few years ago, Terry told him that he no longer wanted to play the witness role. "I am holocausted out," he said.

For how long must he continue speaking of the murder of his mother and sister? How often must he confront his pain? It was likely a meeting with U.S. Ambassador to Germany Richard Grenell that convinced him to make his most recent trip to the camp memorial. The Americans see Terry as one of their own, and Jack Terry wants to do his country proud. He deplores the hatred directed at U.S. Donald Trump, for example, and believes that the media doesn't treat him fairly. Trump, after all, is a strong partner to Israel, having moved the U.S. Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem and recognized Israeli settlements in the Golan Heights.

Recently, survivors, members of their families and numerous guests met in Flossenbürg to commemorate the camp's liberation 74 years ago. Many Americans also came – literally falling into the arms of 89-year-old Jack Terry.

KZ Gedenkstätte Flossenbürg

The visitors walked from the roll call grounds to the back part of the camp where stone stairs descend into the Valley of Death. From above, you can look down on the grave markers, a guard tower and the crematorium, inside of which the Nazis burned huge quantities of corpses. Arm-in-arm, Terry and Grenell strode over to a wall where they unveiled a U.S.-funded plaque dedicated to Dietrich Bonhoeffer. The Protestant pastor and resistance activist was executed in Flossenbürg on April 9, 1945 – exactly two weeks before U.S. troops reached the camp. For Grenell, Bonhoeffer is an idol – a "martyr" who "sacrificed his freedom for his convictions."

Jack Terry's face seemed to have turned to stone as he stood next to the ambassador, surrounded by visitors. Some filmed the occasion on their smartphones while others listened in silence. Terry warned of increasing anti-Semitism "in this and other countries." And then he requested a moment of silence for the victims of the concentration camp.

Suddenly, it was completely quiet. Only the quiet singing of birds could be heard from the forest. A peaceful sound. And fragile.